This is Andrew Benedict-Nelson, social change strategist and innovation educator. Each week, I share a question that you and your organization can use to find a new perspective on the toughest problems you face. Reply to the e-mail or comment on the site and we can talk about them together!

NOW FOR THIS WEEK’S QUESTION…

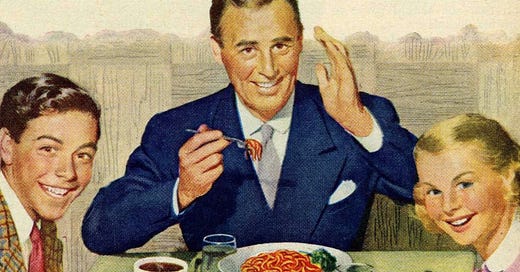

Every problem has a past. People fill that past with stories whether they have any factual basis for them or not. One of those stories that shows up time and time again is the “golden age” of the past, a time before the troubles of today. What do people say about the world before your problem came into being? What assumptions are embedded in that story?

We just can't help it. Human beings tell stories about everything we encounter, and certain elements pop up again and again in those stories whether they make sense or not. Even though very few of us would prefer to live 100 years ago or 1,000 years ago, we frequently talk about the past as if it were a magical world.

The point of this question is not to figure out whether that is happening with your problem — it most certainly is. The point is to learn the specific attributes people believe existed in the world before, why they think they changed, and how that led to your problem. Locked within those stories are ideas about who is to blame and what solutions are or aren’t possible today.

You can change those ideas, but first you have to understand them. Here’s some steps you can take to do that.

HOW TO DO IT

First, you should start by clearing your mind of all the expert knowledge you possess about your problem’s past. Even if you are not a leading authority on the history of your problem, your interest in it has probably led you to educate yourself in facts and perspectives the average person is not aware of. That’s all very good, but it won’t help you for this exercise. So take a moment to close your eyes and let it all go.

Now imagine a single line dividing the world before and after your problem. Think of some words people would use to describe the past and the present. Pay close attention to pairs of opposites or any other words that describe an abrupt change. While you are doing this, you may encounter feelings, symbols, or associations you don’t perfectly understand. Make sure to write these all down even if they don’t make sense to you — remember, this is a mythological distinction between past and present we're describing, not a rational one.

Next, take a look at the descriptions of the past and present and think about what inferences can be drawn about human behavior in both times. For example, people often describe the past as a time of abundance and the present as a time of scarcity, even if there is no empirical evidence for that. What kind of behaviors can we expect to accompany both conditions? See if the inferences fit the story that is told about your problem and where it came from.

Finally, the payoff: identifying assumptions about what kinds of solutions are or are not possible. Because this exercise examines our romanticization of the past, people have often locked all the good things back there and left no resources for our time. But they actually right that our times are so bad? What good things about now are they missing and why? Are the solutions they believe worked in the past even so desirable? Examine the contrast between the past and present until you find an assumption you believe is worth challenging.

CAN YOU GIVE ME AN EXAMPLE?

The “golden age” problem often comes up in discussions of the U.S. political system. People love to tell stories where the leaders of the past were virtuous public servants and today’s elected officials are “just politicians.” Specifically, you often hear stories about how elected leaders in the past were better at listening to each other and striking compromises.

Of course, there’s some truth to these yarns — Ronald Reagan and Tip O’Neill really did work out some deals over drinks. But pay attention to the assumptions built into the contrast. The story assumes that good governance comes from compromise and that compromise comes from elected officials’ personal virtue. That severely restricts ideas about how to change the system from the outside the halls of power.

COOL, SO WHAT MAKES THIS WORK?

This question is an example of how to jump-start creative thinking about your problem using the history dynamic. It’s one of six innovation dynamics I help people master to improve their critical thinking and build strategies for social change. Reply to this e-mail with your answer to the question and I’ll let you know what I think! Or learn more by visiting http://www.teachingsocialchange.com.

.