Find your backbone

Care institutions must reprioritize universal human rights

Last week I wrote about how an ethic of care provides continuity in the time of change we now face as a nation. This week I’m considering an immediate action caring institutions should be taking to prepare for the incoming administration. Out of necessity, I’ll also be thinking about long-term adaptations in the weeks and months to come. By their nature, my thoughts are directed at those who see the threat posed by Trump and his cohort, but I believe they can also offer an approach to reconciliation between his supporters and the rest of us.

For me, the hardest thing about the recent electoral defeat is Trump’s popular vote majority. Though it may be modest by historical standards, the vote total forces those of us on the other side to reckon with the fact that we — our values, our priorities, our identities — are in the minority. For some of us this is a new feeling, while others have been reckoning with it their entire lives.

Fortunately, in most modern democratic states being in the minority does not mean exile. All modern democracies balance principles of majoritarianism (the person who gets the most votes wins) with a universalist conception of human rights (everyone has a right to vote).

The way American institutions creatively balance these two principles is a hallmark of our culture. For example, public libraries generally stock the most popular books regardless of quality (majoritarianism), but they also protect your right to check out what you wish (universalism). This is one of the reasons why recent attacks on libraries have been so distressing — they show that the universalist side of our culture is under threat.

Political theorists have done lots of thinking about how democracies balance these two elements. In particular, Americans should now be reading what Fareed Zakaria and others have written about illiberal democracy, in which majoritarianism becomes unmoored from universalist principles like the rule of law. Elected officials attacking the democratic process (see Jan. 6) is a sure sign of an illiberal democracy.

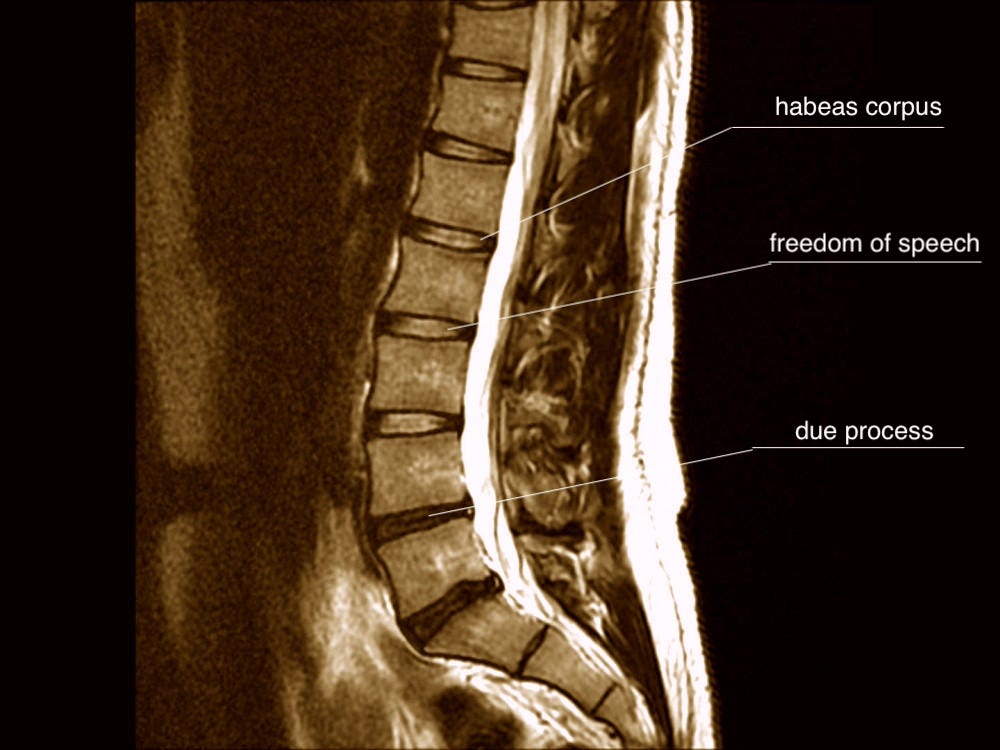

But where does this leave institutions of care? While they have their majoritarian elements, I would characterize hospitals, universities, social service agencies, and similar institutions as a kind of universalist backbone to our fleshy, populist society.

When you enter a hospital, you will be treated using the universal principles of science, not popular opinion (though paradoxically you may also invoke your universal rights to dissent from some parts of scientific treatment). Homeless shelters and food pantries do not ask their clients who they voted for. Both of my parents (nurse and surgeon) had stories of treating people on both sides of a violent dispute. This universalism is essential to who we are as caring professionals, and I have yet to meet the physician or social worker who compromises that based on party affiliation.

Our institutions like to make a similar claim. Many of them have value statements and protocols to that effect. And certainly we have yet to see the deep politicization of caring institutions that nations under authoritarian rule contend with.

But remember, the commitment to universal human rights is not measured by the experience of the average patient, client, or students. It has to be measured by the most marginal cases, and those are the cases I am most worried about in the coming administration.

Let’s use the most immediate threat, a program of mass deportation of immigrants. (I am not characterizing this as “undocumented immigrants” because such a dragnet would catch up legal immigrants and citizens, and their rights are among those we are trying to protect.) This kind of program would inevitably lead to conflict between police forces and any institution that keeps records or houses humans. Imagine this infamous Utah case of conflict between a nurse and police scaled up by the thousands.

You are probably already imagining other types of conflict that enter our institutions: reproductive rights, LGBTQ+ rights, custody battles, sexual violence. We have every reason to believe these conflicts will escalate in the coming years.

This is the context in which institutions should re-examine their commitment to human rights in protocol, policy, ethics, and law. What are the rights of a patient being pursued by the police? What are the rights of a child whose opinion on their gender differs from their parents? How should educators and librarians respond to legislation or executive actions that are plainly unconstitutional? These are not just questions for the legal department, though they should certainly be involved. We need to collectively address these questions as caring professionals in order to preserve our values.

Most MAGA voters may scoff at these concerns as “woke,” but I believe there is a sufficient number of reasonable people on both sides that these kinds of conversations could begin at most institutions before the next administration begins. That’s because conservatives have also for many years benefited from universalist conceptions of human rights within American institutions. A Trump-supporting biology professor may be unpopular among his colleagues, but most of them would defend his right to his opinion. Conscience clauses and religious exemptions are evidence that this discourse isn’t just about liberal snowflakery.

But I would invite conservatives to this conversation for a most immediate and visceral reason: surely you can see we are afraid. Immigrants are afraid. LGBTQ+ people are afraid. Your colleagues and patients are afraid, either for themselves or for people they love. And even a white cisgender man like me is afraid that there is no place for me in the future of my country.

I’ll use my privilege for a minute and address our Republican colleagues directly. We aren’t afraid of the future. We aren’t afraid of a political loss. We aren’t afraid of facing difficult problems.

We are afraid of you.

We are afraid that your political choice shows you support values that will make it impossible for us to do the work of care together. I know plenty of individual Trump supporters and do not feel this fear with them in our daily interactions, as serious as our disagreements may be. No, what scares me most is that one day when I assert what I thought were universal values, I’ll hear silence from people I thought I could trust.

Give us a reason to trust you again. Let’s rediscover the core values we share, then guard them against whatever may come.

When you assert what you think are universal values, you won't hear silence from people you think you can trust. You will hear support and a willingness to stand side by side with you.